| 일 | 월 | 화 | 수 | 목 | 금 | 토 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 |

- 크리에이터 이코노미

- 영단어

- 역사

- 고대문명

- 고대 그리스 로마

- 고대로마

- 고대 그리스 로마 조각상

- 영어공부하기

- 불어문장

- 헬레니즘 미술

- 불어 조금씩

- 고고학

- 영어공부

- 고급 영어

- 불어중급

- 아마르나

- 페니키아

- 고대 이집트

- 루브르 박물관

- 고대 문명

- 영어표현

- 로마제국

- 르네상스

- 고대 로마

- 고대 로마사

- 불어공부

- 영어 공부

- 로마 역사

- 고대 그리스 로마 문명

- 불어 문장

라뮤엣인류이야기

INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT THE DEVELOPMENT OF WRITING SYSTEM IN THE MESOPOTAMIA 본문

INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT THE DEVELOPMENT OF WRITING SYSTEM IN THE MESOPOTAMIA

La Muette 2020. 11. 19. 23:18How does the development of writing systems relate to the wider pattern of social change?

According to Schmandt- Bessearat (1996, p.101), the invention of writings brought about a transitional change from the hunter-gatherer society to ranked society. Also, many scholars (Nissen, Damerow and Englund 1993; Postgate, Wang and Wilkinson 2011; Michalowsky 1994; Powell 2012) share a common opinion that early writings, particularly in early Mesopotamia, were used for accounting and accountability which led to administrative and bureaucratic society.

In this essay, we will particularly focus on the earliest Mesopotamian writing which is best preserved archaeologically. The earliest Mesopotamian writing is only the source we can identify the utilitarian and economic contents; whereas most of ancient early writings in Egypt, Mesoamerica and China are for the purpose of ceremonial and propaganda display (Postgate, Wang and Wilkinson 2011, p. 464). Therefore, the earliest Mesopotamian writing is the obvious source to uncover the wider pattern of socio-economic change in Mesopotamia until the emergence of literary texts in 2500. BC when writing remained as a tool of intensification of elite group's social status.

This essay will discuss the development of writings in the early Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium BC in relation to the process of social change. First, we will examine archaeological evidence of writing from the city-state, Uruk in Southern Mesopotamia. Second, we will discuss the socioeconomic implications of writings in Mesopotamia with scholarly interpretations.

Archaeological evidence of writings in 4th millennium Mesopotamia

The best known archaeological site, in terms of the dramatic socio-economic change, is a city-state, Uruk in the Southern Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq. The site was excavated by the German Archaeological Institute between 1928 and 1976 (Englund 1998, p. 18). During the late Uruk period (ca.3350-3100 BC), it appeared the extraordinary changes which manifested by the settlement evidence of rapid urbanisation and dramatic population growth (Woods 2015, p. 36). The estimated size of settlement area is over 250 hectares in which a sizable part of the city comprises of a large number of public and religious buildings (Finkbeiner 1991, p. 194).

The distinctive characteristics of the site are in the extensive amount of the archaic texts which dated around ca. 3700 and 3100 BC (Woods 2015:36). Such writing evidence is considered as an essential source to demonstrate the dramatic urban change in Uruk (Englund 1998, p. 39). The texts are written in various forms of writings including seals (stamp and cylinder type), token, clay envelope, numerical tablets and pictographic tablets (Figure 1). The frequently appeared in the contents of the texts written on clay tablets are pretty much related to economic function as the abstract numerical signs inscribed on the tablets. In contrast, the rest of forms of writing chiefly describes symbol signs (such as geometric motifs), fishes and animals, but they also still functioned as economic tools (Leick 2001, p. 34).

- Stamp and cylinder seals

Two types of seal, stamp and cylinder (Figure 2) are identified in Uruk. These seals are characterised by the depictions of animals, fished, geometries and the scenes such as craft production, workers in front of a granary, scribes, priests, archer and captives with arms bound. Particularly, the scenes such as labourers in craft production and granary seem to associate with the possible existence of complex and stratified society.

From stamp seal’s earliest appearance in the late seventh millennium BC, they were used to mark property through, their impression into clay that sealed doors, jars, or other packages (Leick 2001, p. 34). Stamp seals continued in use into the Late Uruk period (3350-3100 BC), when they were largely replaced by cylinder seals, perhaps because move varied and complex scenes could be carved into their surface, and perhaps because being rolled, they could cover a larger area of sealing clay (Woods 2015, p. 35).

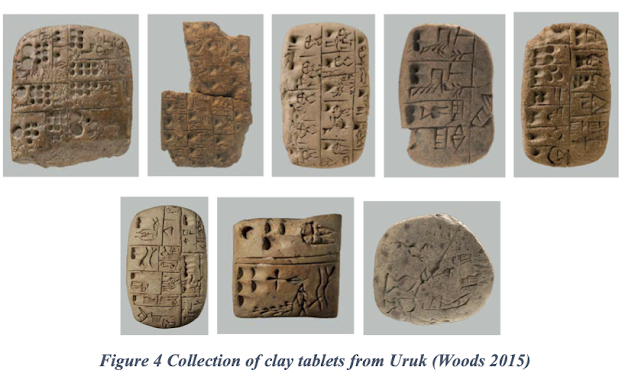

- Clay tablets

Most clay tablets are appeared to be dated conventionally ca. 3200 and 3100 BC (Uruk IV and III phase) (Woods 2015, p. 71). Above all, the 90 percent of around 6,000 Uruk clay tablets are administrative in character and the rest of 10 percent simply listed categories of the contents such as fish, textiles, vessel, animals and birds (Ferioli and Fiandra 1994, p. 155). Further, the archaic texts between ca. 3200 and 3100 BC in Uruk indicate the more complex society would have been existed than before because of the information described in the texts; for example, list of titles and occupations, writing exercise, list of livestock, grain transactions, theoretical calculation of grains, list of rations, amount of barley needed for a given field area, transfer of slaves and goats (Figure 4). Considering those listed information, we can assume how the city-state of Uruk very complex and stratified was.

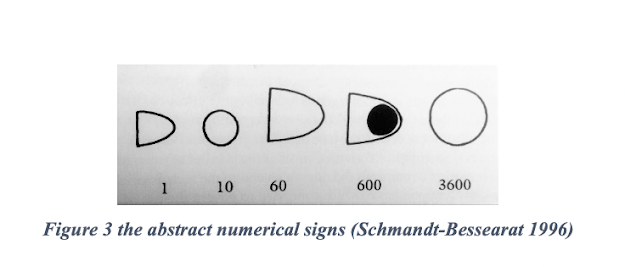

In addition to the contents of depictions and texts, the tablets are distinctively distinguished from the previous earlier depictions in seals and tokens which illustrate only basic symbol and pictographic signs; on the contrary, the tablets describe not only symbols and pictographic signs but also abstract numerical signs (Figure 3). Perhaps, the emergence of abstract numerical signs implies that there was the systematic management of quantifying the number of commodities such as grains and copper, slaves and animals (Michlowsky 1994, p. 54).

Socioeconomic implications of the development of writings

As we have examined the evidence of writings including seals and clay tablets, we have identified that these are pretty much related to the economic purpose of writings which capable of the efficient management of commodities. In this regard, we can assume some socio-economic implications associated with the development of writings.

First, we need to consider that the writing appeared in responding to social pressure and needs. Schmadt-Bessearat (1992) suggest that the invention of writing systems brought about the social change from ‘Egalitarian society’ to ‘Ranked society’. She argues that there is no archaeological evidence for accounting during the Palaeolithic period (Schmadt-Bessearat 1992, p. 103); besides, hunter-gatherer economy does not rely on the accumulation of food resources, rather it relies on daily catches (Meillassoux 1973, p.189). Therefore, there should have been no needs of elaborate counting systems and recording systems in so-called ‘Egalitarian society’ in prior to the rise of a formal and complex social organisation (Bessearat 1992, p. 103).

With the advent of farming society, food accumulation emerged, and an effective distributive system would have been necessary by a central organisation for maintaining stability in village farming communities (Fried 1967, p. 109). Redman (1978, p. 203) argues that elite groups controlled a redistributed economy, and acted as the central collector and redistributor. Consequently, ranked society emerged for the efficient management of the food surplus, thus accounting and recording systems must have been introduced to keep tract of entries and withdrawals of commodities. At this point, supposedly, seals and tablets contributed for establishing the bureaucratic and administrative organisation. Administrators used seals as locks, and they were retained for audits (Ferioli and Fiandra 1979, p. 31). Also, seals were utilised as the verification of the authority of goods distribution, much like a modern signature (p. 31). In the case of clay tablets, it would allow keeping the information of transactions of commodities (Rothman 2004, p. 84).

Second, the use of tablets in durable materials and numerical signs suggest the large scale of economic activities were systematically managed by a central organisation. With the invention of clay tablets, such a new recording system was parallelly used together with cylinder seals during the Late Uruk Period (Woods 2015, p. 44). Presumably, elite rulers in temple or palace would have attempted to manage the commodities of transactions, labours, slaves, etc. more ‘systematically’ by recording in clay tablets.

Particularly, the use of abstract numerical signs in the clay tablets reflects that a large scale of economic activities took place and was managed by the central organisation of a city-state. In fact, the act of counting had been existed by using tokens and clay envelopes which are capable of one to one correspondence counting system (Schmandt- Bessearat 1996, p. 101). However, this type of counting would not appropriate for a large number of commodities and complicate transactions. In around 3200 BC, the counting system by using tokens and clay envelopes were replaced by clay tablets (p. 101).

Eventually, the abstract numerical signs expressing 1, 10, 60 and 360 were impressed as images on the surface on a tablet (p. 101). These were the first symbols representing numbers abstractly and independently from the item counted (p. 101). These first numerals consisted of impressing signs formerly used to indicate the measure of grain and numbers of animals which, from then on, carried a new abstract meaning (Schmandt- Bessearat 1996, p.101). Thus, concerning the size of the highly urbanized settlement of Uruk, to some extent, using the abstract numerical signs would have contributed for the efficient management of the city-state which should have an increasing need of organizing taxation, storage, and redistribution of evident and traded commodities; also, using numerical system enabled the development of more elaborate administrative systems than when only using seals and tokens (Reichel 2013, p. 49).

Perhaps, such economic transactions with the numerical signs would also have been recorded by private traders (Rothman 2004, p. 99). However, because the archaeological excavation tends only to focus on temple or palace districts, it is almost impossible to discover the writings used in mundane and private purpose. Postgate (2011, p. 464) suggest that “Mundane and private writing would have been written in cheap and perishable materials; thus, it is not survived archaeologically; on the other hand, baked clay tablets which made of durable materials and expensive, tend to survive well archaeologically”. Also, he suggests that baked and unbaked clay tablets which, presumably, would have different digress of administrative importance to keep in temple or palace (Postgate, Wang and Wilkinson: 2011, p.464). Accordingly, the survived texts are likely to represent the most important economic transactions in a central organisation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, when considering the archaeological evidence with its scholarly interpretations, the development of writings is strongly tied to the wider pattern of social change. We have examined archaeological evidence of the earliest writings of Uruk in Mesopotamia which dated from ca. 3,700 to 3100 BC. The earliest writings are not in literary form based on phonetic writings, but in simply pictographic and numerical signs which mainly represent the economic function. We have identified that the writings in seals and the clay tablets developed in different periods; that is, seals appeared earlier, and clay tablets appeared in the later periods. Regarding the socio-economic implications, the various writing forms seem to emerge in respond to the need of social change. It is suggested that the invention of writing in Mesopotamia is related to the social change from egalitarian society to ranked society; because, with the surplus of foods, there would have been necessary for a central organization to manage it efficiently. In turn, the writings were used as the administrative and bureaucratic tool. This argument seems more likely when considering the use of clay tablets and numerical signs. Because use of durable materials and the certain type of numerical signs suggest the presence of a central organisation which systematically engaged in the large scale of economic activities.

Briefly explaining the Mesopotamian writings in later periods, particularly, use of abstract numerical signs seems to become the foundation of the development of writings into the literary texts which would bring the different phase of social change (Schmandt-Besserat 1996). Further, during the Early Dynastic (ED) period (ca. 2900-2400 BC), early writing in Mesopotamian transformed from a record keeping technology into a mode of linguistic expression based on the phonetic sounds (Woods 2015, p. 45). The more elaborate writing systems in ED period was used as the political justification tool of elite groups to legitimize their power and social order by means of producing ceremonial and religious texts (Goody and Watt 1963, p. 314).

Bibliography

Englund, R. K., (1998) “Texts from the Late Uruk period.” In , J. Bauer, R.K. England and M. Krebernikn (eds.). Mesopotamian: Spaturuk-Zeit und Fruhdynastische Zeit, Orbis Bibilcus et Orentalis 160/1. Freiburg: Universitatsvelag;Gottingen: Vandenhoeck and Rprecht. pp. 15-233

Fried, M.H. (1967) The Evolution of Political Society: An Essay in Political Anthropology, New York: Random House, p. 109

Ferioli, P., and Fiandra, E. (1994). Archival techniques and methods at Arslantepe. In Ferioli, P., Fiandra, E., Fissore, G., and Frangipane, M. (eds.). Archives Before Writing, Scriptorium, Torino, Italy, pp. 149-161

Finkbeiner, U. (1991). Uruk: Kampagne, 1982–1984; Die archäologische Oberflächenuntersuchung. 2 vols. Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka Endberichte 4. Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, pp. 35-37

Goody ,J. and Watt, I. (1963) 'The Consequences of Literacy', Comparative Studies in Society and History, 5(3), pp. 304-345.

Leick, G. (2001) Mesopotamia: The invention of the City, 1st edn., London: Penguin Books.

Michalowski,P. (1994) “Early Mesopotamian Communicative Systems: Art, Literature, and Writing”. In A. C. Gunter (eds.), Investigating Artistic Environments in the Ancient Near east, Washington, DC, and Madison: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, pp.53-69.

Meillassoux, C. (1973) “On the mode of Production of the Hunting Band” In Pierre Alexandre, (ed.), French Perspectives in African Studies, London: Oxford University Press, pp. 189-194

Nissen, H. J., Damerow, P. & Englund, R. K.(1993). Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Ecnomic Administration in the Ancient Near East. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Powell, B.B (2012) 'Origin of Lexigraphic Writing in Mesopotamia', in Powell, B.B (ed.) Writing Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 70-84.

Postgate, N., Wang, T., Wilkinson, T. (1995) 'The evidence of early writing: utilitarian or ceremonial?', Periodicals Archive Online, 69(264), pp. 459-480.

Reichel, C. (2013) 'The Bureucratic Backlashes: Bureaucrats as Agents of Socioeconomic Change in Proto-Historic Mesopotamia', in Englehardt (ed.) The Agency in Ancient Writing. Colorado: University Press of Colorado, pp. 45-54

Redman, C. L., (1978) The rise of Civilization, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, p.203

Rothman, M. S. (2004). Studying the Development of Complex Society: Mesopotamia in the Late Fifth and Fourth Millennia BC. Journal of Archaeological Research 12(1), pp. 75-119

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (1996) How writing came about, 2nd edn., Texas: The University of Texas press.

Woods, C. (2015) 'The Earliest Mesopotamian Writing', in Woods, C., Teeter, E. and Emberling, G. (ed.) Visible Language: Inventions of writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond. Chicago: The Oriental Institute, pp. 33-84.